Silvia Irina Zimmermann: The Ideal Sovereign

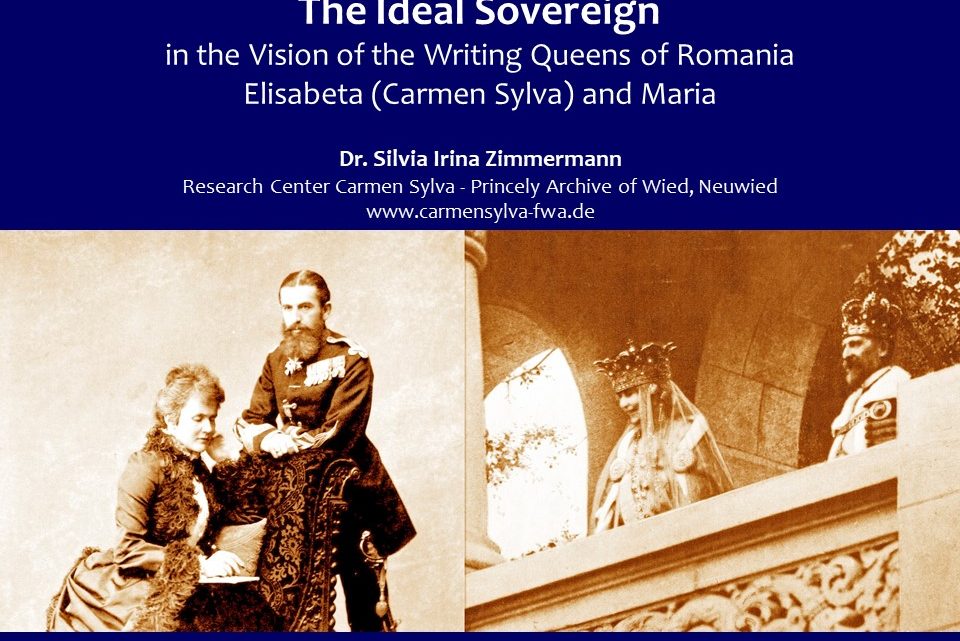

The Ideal Sovereign in the Vision of the Writing Queens of Romania, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) and Marie

by Silvia Irina Zimmermann*

The history of the monarchy in Romania and of its four kings would be incomplete without the story of the queen consorts, who seem to have been even more fascinating personalities than the kings. The first two queen consorts, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) and Marie of Romania, became famous as writers during their lifetime. They both wrote in their mother tongues, Elisabeth in German and Marie in English, and published many of their books, not only in Romania, but also abroad, thus reaching a widespread readership, worldwide publicity, and literary recognition.

Besides their fictional writings, the first two queens of Romania, Elisabeth and Marie, also wrote memories and diaries. Queen Elisabeth signed both her published literary books and her memoirs with her pen name Carmen Sylva, in order to mark a difference between the writer and the queen. Queen Marie, instead, simply used her royal title for her publications with no need to express any difference between the author and her high status. Nevertheless, both the works of the Poet-Queen Carmen Sylva as well as those of Queen Marie contain their reflections about how an ideal sovereign should be and which living royal personality they considered mostly alike to their vision.

Both queens were writing their memories in their native language (Elisabeth in German, Marie in English) and they published their books in their native country (Germany and the United Kingdom), as well as in Romanian translation in the country of their destiny, Romania. Like in the fairy tales, in their autobiographical writings about their kingdom the queens are describing the rich beauties of Romania, its landscape, the rural and monastic architecture, showing their empathy with the Romanian people, and inviting the foreign reader to share their high hopes for their country. While both writing queens describe King Carol I of Romania as a strong personality and a great king, his successor on the Romanian throne, Crown Prince and later King Ferdinand, is either missing (like in Elisabeth’s writings), or he is barely mentioned (like in Marie’s writings). Thus, for the Poet-Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) King Carol I is the embodiment of the ideal monarch, while Queen Marie is promoting herself as the caring and visionary sovereign.

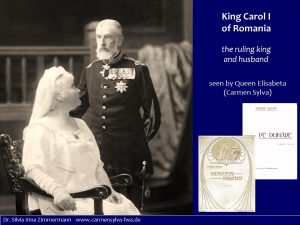

King Carol I of Romania, the ruling king and husband, seen by Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva)

In several writings, Queen Elisabeth is focusing on her husband, King Carol I of Romania, and showing him as a devoted monarch who fought to change Romania’s status from a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire into an independent state and a new kingdom and who supported Romania’s development in economy, culture, arts, society, and technology.

In her essay Bucharest (1893)[1], Queen Elisabeth tells the story about the young prince Carol who, when being offered the crown of Romania in 1866, saw the future of the country in a vision of achievement und fulfillment:

“When the crown of the country, of the very existence of which he was ignorant, was offered to a young Hohenzollern prince, he opened the atlas, took a pencil, and seeing that a line drawn from London to Bombay passed through the principality which called him to be its head, he accepted the crown with these words: ‘This is a country of the future!’”[2]

The same story is repeated in the later published book Rheintochters Donaufahrt (1905) – the German title meaning: “The Daughter of the Rhine Travelling on the Danube”, the Romanian title being: Pe Dunăre, i.e. “On the Danube”. In Rheintochters Donaufahrt / Pe Dunăre (1905) Queen Elisabeth describes the journey of the Royal Family on the Danube in May 1904.[3] The German title seems to emphasize the importance of the author herself, pointing out that it is Elisabeth, the former princess from the Rhine, sharing her memories about her new country. Nevertheless, her book is more about her husband King Carol I. Elisabeth is relating her observations about the landscape, the people and events along the Danube, while mixing them up with reflections about the life and visions of her husband, the King, and thus bringing out his achievements during his long reign in Romania. From all the achievements of the king, she specifies, Queen Elisabeth considers the bridge across the Danube to be the most important realization of her king and husband, because this symbolized for Romania a bridge to worldwide trading:

“Now we arrived at Cernavodă. I have been there already when the bridge was officially opened. To me, this was the most touching day of the king’s whole reign. When he was offered the Romanian crown, he did not know yet anything about the country and he already had refused other crowns, where he could see no future. But now, he opened a map, took a pen, drew a line between London and Bombay and saw that it was passing through Romania. Then he accepted the crown. When I married thirty-five years ago, I saw the first plans for the bridge across the Danube lying on his desk. But he had to wait for thirty years, until his plan could be accomplished. […] And when the bridge was ready, the King solemnly hit the last nail. […] And that was the moment when I realized that the King had just fulfilled his mission. Right there, at the bridge of Cernavodă, was now the next connection between London and Bombay. It was this bridge that counted, and that we had waited for thirty years. […] Hitting the last nail in the bridge across the Danube was the quintessence of [our] whole life.”[4]

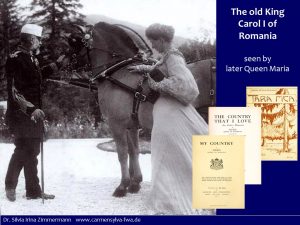

King Carol I of Romania seen by later Queen Marie

In Queen Marie’s book, The Country That I Love[5] (1925), there are several passages about the old King Carol I, too. Like the Queen consort Elisabeth in her book Rheintochters Donaufahrt / Pe Dunăre (1905), Queen Marie emphasizes a good relationship with “the old King Carol” and imitates the way Elisabeth herself evoked the king’s confidence in his wife, when he was sharing his thoughts, plans, and visions with her. More than that, Queen Marie somehow puts Queen Elisabeth down, when saying that the king did not ask for his wife’s advice and did not value her opinion as to consult her when he planned and decorated the Pelesh-Castle in Sinaia and the Royal Palace in Bucharest. According to the lately published correspondence of the royal couple Carol I and Elisabeth, the first queen of Romania was a confidant of King Carol I and the letters of the king to his wife show that he very much valued Queen Elisabeth’s opinion and that they shared with one another not only family issues but also information about social and political matters.[6]

Nevertheless, Queen Marie of Romania leads the reader of her memoires to see herself as the only one who was a true confidant of the old king in the Royal Family and that he somehow considered Marie a conversation-partner at eye-level. Like Queen Elisabeth[7], the later Queen Marie also calls the old King Carol her teacher and friend:

Nevertheless, Queen Marie of Romania leads the reader of her memoires to see herself as the only one who was a true confidant of the old king in the Royal Family and that he somehow considered Marie a conversation-partner at eye-level. Like Queen Elisabeth[7], the later Queen Marie also calls the old King Carol her teacher and friend:

“How often has he related to me tales of these wanderings, when he visited the most distant corners of his land. His eyes would sparkle, his descriptions become vivid, a smile would brighten the usual gravity of his face; so dear to him was the remembrance of those days of travel and discovery in the country he had come to love. […] Loving this country as I do, I gratefully realize how he, who was our forerunner, showed us the way.”[8] “Later, as my understanding grew, I learnt to appreciate the value of what often had wearied me at first. I entered more entirely into the wise old man’s interests; there was so much knowledge to gain from his experience, and if his judgment was sometimes foreign to my more ardent conception of things, much did I learn from his words, and more still from the example he gave us. […] Never was man more austere, more simple, more selfless, existing solely for his work. A saint could not have lived a life of greater abnegation. We did not always agree, but each year made of us better friends.”[9]

For Queen Marie, the old King Carol was “a great king” with a vision fulfilled and an ideal king for his country – but only up to the point when history changed and he couldn’t go any further fighting for his peoples’ dream, and when he died just before the First World War broke out:

“He too had a dream, but a dream he realized little by little through many long years.”[10] “He had had but one ideal the glory of his country, the good of his people. […] [Now] He was at rest – his work was over and, at an hour when he and his people could no more follow the same dream, the great King closed his eyes and became silent, leaving unto others the solving of the last question – the one that had been taken out of his hands.“[11]

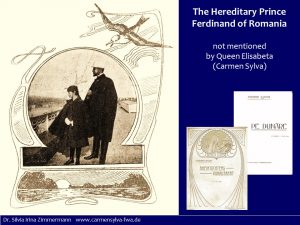

The Hereditary Prince Ferdinand of Romania unmentioned in the works of Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva)

The Hereditary Prince and later King Ferdinand is never mentioned by Queen Elisabeth in her autobiographical writings for the public. Nevertheless, Queen Elisabeth’s private correspondence with her princely family in Neuwied and with her husband, King Carol I, reveals that she was disappointed by the lack of charisma and by the indecisiveness of Prince Ferdinand, the nephew of the king and heir to the Romanian throne.

In the long run, Queen Elisabeth was content to realize that Crown Princess Marie of Romania was the more active and determined part of the couple, and that she had both the power and the skills to continue the work Elisabeth had begun for Romania and to become a good queen consort and the best match for the future King Ferdinand. Thus, in Queen Elisabeth’s book Rheintochters Donaufahrt / Pe Dunăre (1905) about the journey of the Royal Family on the Danube in May 1904, when Prince Ferdinand was part of the travelling family group, he appears only in some of the images in the queen’s book, but otherwise he is not mentioned at all. Instead, Queen Elisabeth writes about the Crown Princess Marie and about the children of the hereditary couple Ferdinand and Marie and focuses on little Prince Carol, the first hereditary prince born in Romania, whom she regards as the high hope of the country and the follower of her husband, King Carol I.[12]

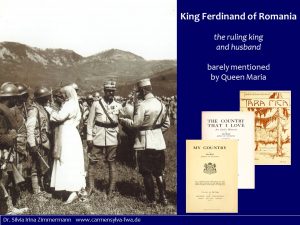

King Ferdinand I of Romania, the ruling king and husband, barely mentioned in the works of Queen Marie

King Ferdinand I of Romania, the ruling king and husband, is barely mentioned by his queen consort Marie, too. In her book, My Country (1916) there is no mention of any king. Here the author Queen Marie introduces herself to the English reader with an emphatic affirmation at the very beginning: “The Queen of a small Country!,” adding that “she would like the country of her birth [England] to see this other country [Romania] through the eyes of its Queen”.[13] When reading this book, one has the feeling that the author Queen Marie is a queen regnant, a queen ruling in her own right, and not just a queen consort.

In Queen Marie’s book The Country That I Love (1925) – a kind of continuation of the book My Country (1916) – and in the Romanian edition Ţara Mea (1917-1919) – containing both My Country and The Country That I Love in Romanian translation – we can find two chapters about the old King Carol and a few passages about King Ferdinand, too. However, in Queen Marie’s second book about Romania, The Country That I Love, King Ferdinand is present, but Queen Marie does not mention his name anywhere. Instead, Ferdinand is simply called “the King” or “The King and I”.[14] Nevertheless, there are two longer passages, where King Ferdinand becomes more a part of the plot in Queen Marie’s book. In the first case, Queen Marie tells about her travelling with the king in the country, while they are both heavy-laden by the thought of the approaching war:

“A heavy feeling of gloom brooded over all things; hearts were uneasy, spirits were troubled, and not least troubled was the heart of the King. Those were days of throbbing anxiety; we knew that the wing of war was already hovering near our country, and, like two anxious parents, we watched the horizon, feeling that the hour of fate was nearing, that naught could now stay the storm that must break over our land. Restless were the King’s nights, sleep avoided him, his soul was torn by doubt. Was it the right moment? If he drew the sword would it be for the good of the country? Would the word he had to say, the word that would cut him off from all the loves of yore, would that word lead his people towards the accomplishment of their Golden Dream?”[15]

Another mentioning of King Ferdinand (again without his name) occurs in Queen Marie’s Romanian edition Ţara mea, when the queen appreciates the appearance of the King and the hereditary Prince Carol, the later King Carol II (also mentioned without his name in Queen Marie’s book), in the field hospital where the queen takes care of the wounded soldiers:

“My husband, who had the command upon all the troops, came every day to see how we were getting along. His presence was a huge encouragement and all our sick people welcomed his arrival as a sign that nothing had been left aside from what they would need. My son was with me, too, my elder son; he was my right hand, my workmate, and his young energy could reach the places where my smile could not.”[16]

Both Queen Elisabeth and Queen Marie have a similar discomfort with Ferdinand’s weaker personality, and seem to compare him with the old King Carol I, expecting from him to have more initiative and to show a more determined attitude towards the people. In consequence, Queen Elisabeth chose not to mention Ferdinand at all in her memoires. Queen Marie, on the one hand, writes about King Ferdinand with respect and sympathy in part II of the Romanian edition of her book. On the other hand, in her diaries, she writes about her being disappointed by the lack of energy and initiative of her husband King Ferdinand and she expresses her wish to take the lead, asking herself: “Oh, why am I not King?”[17]

Regarding the passage in Queen Marie’s book The Country That I Love about the hereditary Prince Carol (“he was my right hand, my workmate, and his young energy could reach the places where my smile could not”[18]) – this is obviously a euphemism, and Queen Marie here seems to be holding the pieces of the royal family together. In reality, the hereditary Prince Carol had not demonstrated the sense of duty and sacrifice for his country expected from an heir, but more of the contrary. In 1918, Prince Carol had deserted to marry Zizi Lambrino on 31 August 1918. In addition, in 1925, when Queen Marie’s book was published in the United Kingdom, Prince Carol would leave his family with a new mistress and renounce his right to the throne on 28 December 1925 in favor of his son by Crown Princess Helen (Elena), Mihai, the later King Mihai I.

Contrastingly, when talking about herself in her book The Country That I Love, Queen Marie emphasizes her strength and courage that caused her to be admired and loved by her people: “Not many princesses and queens are given the chance to be so close to their troops, but because this is a small country, the sovereigns are really taking their part, too. There must be something in my nature that makes me be helpful whenever there is an eager need of help and energy. Then, it’s like my forces grow twice as before and my strengths seem never to vanish.”[19]

In the context of the First World War, the books of Queen Marie about Romania were not meant to pay tribute to the reigning King Ferdinand (who was a German native), but Queen Marie was addressing herself to the reader from her native country, the United Kingdom, who in the World War was fighting against the German Empire. Thus, it is understandable that Queen Marie’s books focused instead on the personality of a queen who not only overshined the defects and drawbacks of both the king and the heir to the throne. More than everything else, her books emphasized that Romania had a determined sovereign fighting for her people’s survival during the war and occupation period. For the English reader of Queen Marie’s books about Romania it must have been more sympathetic that Queen Marie, an English princess, was bound both to her native country, the United Kingdom, and to her new country Romania, who also was an ally in the war. And for the Romanian reader Queen Marie of Romania embodied the ideal sovereign for Romania more than anybody else, as she not only pictured herself as a monarch determined to fight for her people’s dream, but also acted during the war time like a monarch capable of sacrifice for her country, and a devoted monarch, one could rely on.

Regarding the personal understanding of their role as queen consorts, the writing queens of Romania, Elisabeth and Marie, reveal different kinds of images of a queen, though they have the same intent of reaching a large public and both have great power of persuasion.

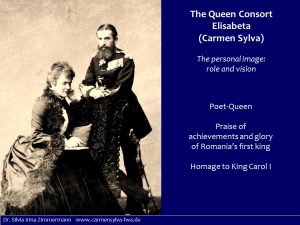

The Queen Consort Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva): The Personal Image of Her Role and Vision

Queen Elisabeth considers herself a poet-queen and a chronicler writing about the visions and the glory of the first King of Romania, and bringing homage to King Carol I. Queen Elisabeth had dreams and visions, too: She badly wished to have an heir and she had the vision of having a royal court at Bucharest with a high cultural prestige. In the end these would all be dreams, which did not fulfil as she expected.[20] Instead, Queen Elisabeth had no heir, and after the death of her only daughter no further children. She went through the bitter experience of a three-year long exile (1891-1894), followed by the loss of her influence at court and the downsizing of her importance and historic memorability – as one can also notice from the portrait made by later Queen Marie, who called the dreams of old Queen Elisabeth ironically: “building castles in the air”[21].

Elisabeth and Marie had a quite difficult relationship at the beginning. In 1893, when Marie became the hereditary princess of Romania, Elisabeth felt like being brushed aside by the young princess, who had taken her place at the Royal Court in Bucharest, while Elisabeth was banned to come back to Romania for another two years of her exile.[22] After her return to Romania, Queen Elisabeth began to realize the talents of the crown princess, and she encouraged her literary activity by translating one of her novels into German and writing a foreword to a long fairy tale of Crown Princess Marie.[23]

Nevertheless, long before Marie’s appearance at the court in Bucharest, Queen Elisabeth had the vision to be the chronicler of King Carol I of Romania and she wished to write his memoires. She advised the king of the importance that he, who had won the independence of the country and was the first king of Romania, must publish his memories. Obviously, Queen Elisabeth already made a start in writing about his life, as she asked Carol in a letter from 1890 to continue to make some notes, so that they could write it all together later.[24] However, the implication of Queen Elisabeth encouraging a marriage of the Hereditary Prince Ferdinand with her court-lady Elena Văcărescu in 1891 was a fatal mistake of hers, which finally caused Queen Elisabeth to be exiled for more than three years, from 1891 to 1894. During the exile-period of Queen Elisabeth, King Carol I began to publish his memoires. In addition, the king chose a former literary co-author of the Queen, Mite Kremnitz, to be the editor of his memoires, which was another blow to Elisabeth, who then blamed Kremnitz for having intrigued against her.[25] Maybe as a compensation for all her losses, Queen Elisabeth published her book about the royal journey on the Danube Rheintochters Donaufahrt in 1905, both in Germany and in Romania, thus paying a tribute to King Carol I, and obviously wishing to leave behind a picture of her king and husband in her own words.

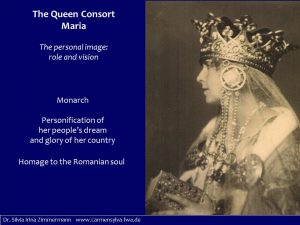

The Queen Consort Marie: The Personal Image of Her Role and Vision

The Queen Consort Marie is presenting herself more self-confident than Queen Elisabeth in her writings: Marie is a monarch writing about her peoples’ “Golden Dream”, the Great Union of Romania. She is a queen fighting with her pen for the glory of her country and paying a tribute to the Romanian soul. Moreover, she pictures herself as an ambassador for her Kingdom, presenting herself and taking an attitude like a reigning queen on her visits abroad when meeting political personalities.[26]

Queen Marie published the book My Country first in the United Kingdom, in 1916, during the First World War. By this time, Marie was the Queen of Romania for just 2 years (the old King Carol I had passed away in October 1914), and beginning with August 1916 Romania was at war, on the side of the Allied Powers. Queen Marie’s book My Country had a note on the front page, too: “All profits from the sale of this book will be paid to the British Red Cross Society for work in Rumania”. Queen Marie published the continuation of My Country under the title The Country That I Love. An Exile’s Memories in 1925 in the UK, and this part was about the war-years 1917-1918 spent by the queen in Jassy, when Bucharest and the South of Romania were under German occupation. There also existed a Romanian edition published in 1917 and 1919, a translation by the historian Nicolae Iorga, containing both books of Queen Marie in one volume and entitled Ţara mea. The Romanian volume had an additional first chapter before part II of the book, about the Romanian soldiers preparing for war and Queen Marie on the field hospitals, a chapter dated 18 August 1916.[27]

Queen Marie published the book My Country first in the United Kingdom, in 1916, during the First World War. By this time, Marie was the Queen of Romania for just 2 years (the old King Carol I had passed away in October 1914), and beginning with August 1916 Romania was at war, on the side of the Allied Powers. Queen Marie’s book My Country had a note on the front page, too: “All profits from the sale of this book will be paid to the British Red Cross Society for work in Rumania”. Queen Marie published the continuation of My Country under the title The Country That I Love. An Exile’s Memories in 1925 in the UK, and this part was about the war-years 1917-1918 spent by the queen in Jassy, when Bucharest and the South of Romania were under German occupation. There also existed a Romanian edition published in 1917 and 1919, a translation by the historian Nicolae Iorga, containing both books of Queen Marie in one volume and entitled Ţara mea. The Romanian volume had an additional first chapter before part II of the book, about the Romanian soldiers preparing for war and Queen Marie on the field hospitals, a chapter dated 18 August 1916.[27]

As a writer, Queen Marie focuses in her books My Country (1916) and The Country That I Love (1925) on her feelings towards the country as her peoples’ land. The reader does not learn anything about real politics, only a few passages about Romanian history, nothing about its educational system, the beginning industry, or people in the towns and the high society, nor can we read anything about the economy and trading relations of Romania with other countries. In this regard, the books of Queen Marie are very different from Queen Elisabeth’s book praising the old King Carol and his achievements in various fields of activity: army, culture, railroad infrastructure, development of the cities, trading, and international politics. Nevertheless, Queen Marie warns the reader right at the beginning about what her book on Romania does not contain:

“I am not going to talk of my country’s institutions, of its politics, of names known to the world. Others have done this more cleverly than I ever could. I want only to speak of its soul, of its atmosphere, of its peasants and soldiers, of things that made me love this country, that made my heart beat with its heart.”[28]

Thus, Marie describes mostly the landscape of the country, revealing her emotions and the atmosphere of what she can see when she visits the peasants in their villages, the nuns and monks at the monasteries. Nevertheless, Queen Marie offers a brief history of the capital city of Moldavia, Jassy, in The Country That I Love (1925) and she describes the castles and palaces in Sinaia and Bucharest, later the Bran castle, the surroundings of Constanţa, and the harbor at the Black Sea. When telling about her own personal dreams, Queen Marie reveals very private and unspectacular joys like the dream to build houses in different beautiful places of her country and to plan new flower gardens. Nonetheless, in regard to her social position as a queen, Marie’s vision is the same as her people’s “Golden dream” of the union of all Romanians in one country. Obviously, Queen Marie is aiming to personify this dream of the Romanians with her attitude as a confident, caring, courageous, and faithful queen of her people. Above all, the two books of Queen Marie, My Country (1916) and The Country That I Love (1925) are an homage to the Romanian land, its people and the Romanian soul, because, as she declares: “There is nothing of the Romanian land that I have not loved. […] I have loved it all, loved it deeply … loved it well!”[29]

For both writing Queens of Romania, Elisabeth and Marie, the ideal sovereign for their country is the caring and visionary monarch. To Queen Elisabeth it is King Carol I of Romania who embodies her ideal of a sovereign, because of all his achievements for the country’s independence, welfare, and prosperity during his long reign. Contrastingly, in Queen Marie’s books, it is the queen idealizing herself as a monarch, who has the strong character and determined attitude to fulfil her country’s dream, the unity of all Romanians. Finally, King Carol I and Queen Marie of Romania appear as monarchs with a vision fulfilled, both gaining greatness through their achievements and attitude.

***

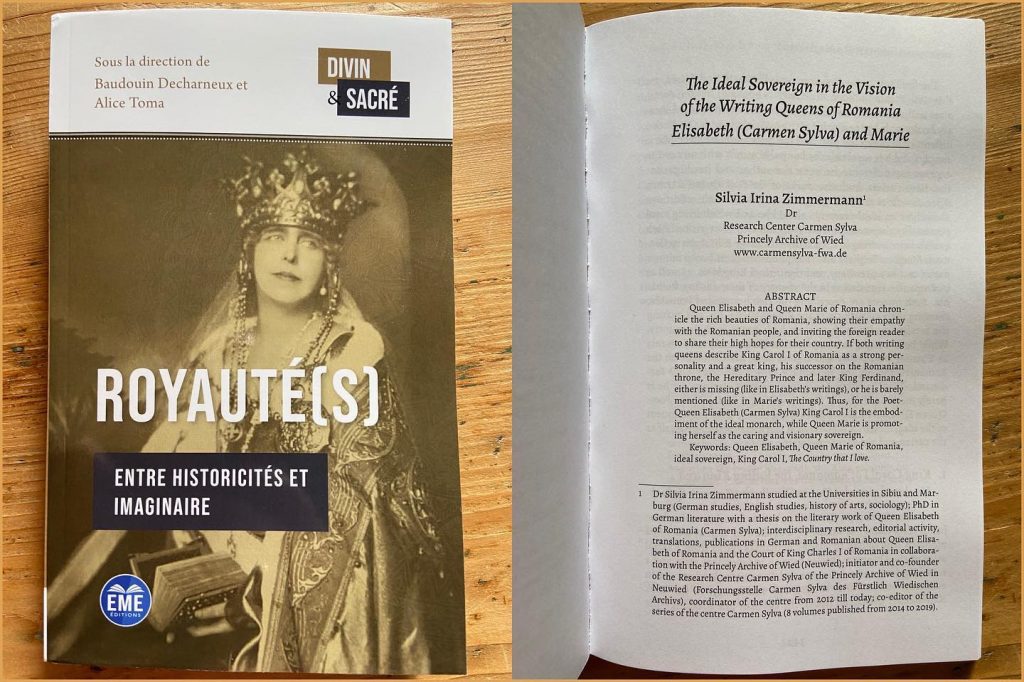

* Chapter from the book:

„The Child of the Sun: Royal Fairy Tales and Essays by the Queens of Romania, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva, 1843-1916) and Marie (1875-1938)“. Selected and edited, with an introduction and bibliography by Silvia Irina Zimmermann. [Series of the Research Center Carmen Sylva – Princely Archive of Wied, vol. 9], 315 pages, 54 illustrations (7 colored), Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag (Ibidem Press), 2020, 315 pages, 54 illustrations (7 colored), ISBN-13: 978-3-8382-1393-4.

„The Child of the Sun: Royal Fairy Tales and Essays by the Queens of Romania, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva, 1843-1916) and Marie (1875-1938)“. Selected and edited, with an introduction and bibliography by Silvia Irina Zimmermann. [Series of the Research Center Carmen Sylva – Princely Archive of Wied, vol. 9], 315 pages, 54 illustrations (7 colored), Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag (Ibidem Press), 2020, 315 pages, 54 illustrations (7 colored), ISBN-13: 978-3-8382-1393-4.

https://www.sizimmermann.de/buch/writing-queens-romania.htm

Presentation held at the International Conference / Colloque international: Royauté(s): entre historicité et imaginaire. Organizers: Académie Royale de Belgique, Maison des arts de l’Université libre de Bruxelles – ULB, Résidence de l’Ambassadeur de la Roumanie. Journées scientifiques d’études roumaines à Bruxelles, October 25-27, 2018.

The article is also published in the conference volume:

Silvia Irina Zimmermann: „The Ideal Sovereign in the Vision of the Writing Queens of Romania, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) and Marie“), in: „Royauté(s): entre historicité et imaginaire“, sous la direction de Baudouin Decharneux et Alice Toma, Louvain-la-Neuve: EME Éditions, 2021, pp. 341-357.

Notes:

[1] A first version of Queen Elisabeth’s essay about Bucharest in French was published in: Les Capitales du Monde, 1892, nr. 12, Paris, p. 297-320; the English translation appeared in: Haper’s weekly, Saturday, February 4, 1893, New York, vol. XXXVII, No. 1885, p. 107-111; and the German version in: Die Hauptstädte der Welt, Breslau: Schottländer, [1898], p. 403-430.

[2] Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva): Bucharest, in: Haper’s weekly, New York, 1893, p. 111.

[3] Carmen Sylva: Rheintochters Donaufahrt, Regensburg: Wunderling, 1905. Carmen Sylva: Pe Dunăre, Bucureşti: Socec, 1905. Two new editions of the journal are published in: Silvia Irina Zimmermann: Unterschiedliche Wege, dasselbe Ideal: Das Königsbild im Werk Carmen Sylvas und in Fotografien des Fürstlich Wiedischen Archivs, Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag, 2014, p. 113-175. Silvia Irina Zimmermann: Regele Carol I în opera Reginei Elisabeta, Bucureşti: Editura Curtea Veche, 2014, pp. 152-199.

[4] Carmen Sylva: Rheintochters Donaufahrt (1905), p. 51-52 and p. 70. Quote translated from the German by S. I. Zimmermann.

[5] Queen Marie of Romania: The Country That I Love (1925), p.45-70.

[6] See more in: Silvia Irina Zimmermann (editor): „In zärtlicher Liebe Deine Elisabeth“ – „Stets Dein treuer Carl“. Der Briefwechsel Elisabeths zu Wied (Carmen Sylva) mit ihrem Gemahl Carol I. von Rumänien aus dem Rumänischen Nationalarchiv in Bukarest. 1869-1913, Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag, 2018, especially volume I, containing the royal correspondence from the period 1869-1890. Silvia Irina Zimmermann: “Corespondenţa primei perechi regale a României, Carol I şi Elisabeta, păstrată la Arhivele Naţionale ale României din Bucureşti”, in: Revista Bibliotecii Academiei Române, Bucureşti, Anul 3, Nr. 1, ianuarie-iunie 2018, p. 3-21.

[7] Zimmermann: Unterschiedliche Wege… (2014), see chapter: Der Lebenspartner (The Life Partner), p. 59-73, especially p. 67-73.

[8] Queen Marie of Romania: The Country That I Love (1925), p. 59-60.

[9] Ibidem, p. 52-53.

[10] Ibidem, p. 46.

[11] Ibidem, p. 54.

[12] For more details see: Silvia Irina Zimmermann: “Portretul perechii princiare moştenitoare Ferdinand şi Maria din viziunea Reginei Elisabeta a României în scrisori personale şi texte pentru publicul larg”, in: Revista Bibliotecii Academiei Române, Anul 1, Nr. 2, 2016, p. 11-35.

[13] Queen Marie of Romania: My Country (1916), p. 5 and p. 6.

[14] Queen Marie of Romania: The Country That I Love (1925): “the King and I”, p. 41; “the King”, p. 42. The only place where the name of King Ferdinand is appearing in Queen Marie’s book is in the obituary for their son Mircea (p. 152).

[15] Queen Marie of Romania: The Country That I Love (1925), p. 42.

[16] Regina Maria: Ţara Mea (1919), p. 97. Quote translated from the Romanian by S. I. Zimmermann.

[17] Lucian Boia (editor): Regina Maria: Jurnal de Război, 1916-17, the Queen’s note from Sept. 25/ Oct. 8, 1916, p. 164.

[18] Regina Maria: Ţara Mea (1919), p. 97.

[19] Ibidem, p. 102. Quote translated from the Romanian by S. I. Zimmermann.

[20] For more see in: Zimmermann (ed.): Der Briefwechsel… (2018), volume II: 1891-1913, p. 65; p. 384.

[21] Queen Marie of Romania: The Country That I Love (1925), p. 68.

[22] More about the exile of Queen Elisabeth in: Silvia Irina Zimmermann: “Corespondenţa primei perechi regale a României…” (Revista Bibliotecii Academiei Române, 2018), p. 3-21. Silvia Irina Zimmermann: “Activitatea literară şi artizanală a Reginei Elisabeta din perioada exilului (1891-1894) în oglinda corespondenţei cu Regele Carol I. Colaborarea reginei cu André Lecomte du Noüy”, in: Revista de Artă şi Istoria Artei, Bucureşti: Editura Muzeului Municipiului Bucureşti, Nr. 1, 2018, pp. 144-159.

[23] See more in: Hannah Pakula: The Last Romantic: A Biography of Queen Marie of Roumania. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984, p. 66–67, p. 103-104, p. 122-123, p. 143. Gabriel Badea-Păun: Carmen Sylva. 1843-1916. Uimitoarea regină Elisabeta a României, Bucureşti: Humanitas, 2010, p. 204-206, p 210-211. Gabriel Badea-Păun: «Autour d’un récit autobiographique royal», dans: Reine Marie de Roumanie: Histoire de ma vie. 1875-1918, Paris: Lacurne, 2014, p. 9-19, especially p. 13-14. Silvia Irina Zimmermann: „Die Feder in der Hand bin ich eine ganz andre Person.“ Carmen Sylva (1843-1916). Leben und Werk, Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag, 2019, p. 305-312, p. 315-335.

[24] Zimmermann (ed.): Der Briefwechsel… (2018), volume I: 1869-1890, p. 342-343.

[25] More about the relation of Queen Elisabeth and Mite Kremnitz in: Zimmermann: Carmen Sylva. Leben und Werk (2019), p. 11, p. 164. Zimmermann: Unterschiedliche Wege… (2014), see chapter: Über den Herrscher in republikanischen Zeiten (On the Sovereign in Republican Times), p. 89-104, especially p. 89-93. Silvia Irina Zimmermann: „Despre regi in vemuri republicane. Portretul regelui în opera reginei Elisabeta a României”, in: Claudiu-Lucian Topor, Alexandru Istrate, Daniel Cain (editori): Diplomaţi, societate şi mondenităţi. Sfârşit de Belle Époque în lumea românească, Iaşi: Editura Universităţii Alexandru Ioan Cuza, 2015, p. 125-138.

[26] More about the political talent of Queen Marie of Romania and her visits abroad in: Adrian-Silvan Ionescu: Regina Maria şi America, Bucureşti: Noi Media Print, 2009. Diana Mandache: Viva Regina Maria! Un destin fabulous în reîntregirea României, Bucureşti: Editura Corint, 2016.

[27] Regina Maria: Ţara Mea (1919), p. 89-105.

[28] Queen Marie of Romania: My Country (1916), p. 8.

[29] Queen Marie of Romania: The Country That I Love (1925), p. 18-19.